OCHRE MINE By Lisa Moren

Panorama Injet, 36”x 144” [ detail, mounted ]

North of Flinders Ranges, Songline or “Dreaming Path” for the Diyari people, SA, South Australia, 2012.

I was invited by the Artists Research Network of La Trobe University in Melbourne, who knew of my pigment projects on the Chesapeake Bay and requested I repeat the project there. As I was looking at waterways, I kept returning to a story I had read about the Diyari [Dieri], the first nations people of the South Australian outback.

OCHRE WARS

Every July and August, for possibly thousands of years, 70 or 80 of the strongest men from the Diyari tribe walked several hundred kilometers, 30km per day from their native home in the Lake Eyre region to Parachilna north of Flinders Ranges [more than 320 km total, Mulvaney]. The men were heavily armed on their journey to collect a the highly valued and sacred red-gold pigment. The Diyari were the exclusive owners of the secret location and the techniques to extract some of the best ochre on the continent. It’s said the pigment had a shimmery and creamy texture, even iridescent [possibly from mercury], and was savored for the most sacred rituals. The men ground the red rock into a powder, and then used water or urine as a binder for cakes, and wrapped it in grass and human hair. Each man carried the 20-35 kilos worth of bricks back to Lake Eyre where the entire tribe survived on trading the ochre for the rest of the year.

For possibly thousands of years, this annual pilgrimage was made until 1860 when the “whitefella” sheep farmers arrived and came into direct conflict with the Diyari. The Diyari were hunting the farmer’s sheep for food, a crime at the time punishable by hanging. These were followed by counter-reprisals by the Diyari, which became known as the Ochre Wars. At the time, the main British administration was in the city of Adelaide, South Australia, these English leaders were keen to end the ochre conflict. It must be noted that to the Diyari, the path they walked was their rightful path and was as sacred as it was economical. Because the Diyari were responsible for the land, any fences, homesteads, animals, etc., were free for the taking along their inherited path.

Throughout the 1860s there was hostile violence from both sides, and eventually, someone in Adalaide suggested a solution. I want to get to that solution later, because simultaneously, in nearby Victoria, is another kind of mining, gold. This mining story follows a more familiar scenario of a gold mining rush that was so successful that it lead to the foundation of Australia’s first stock exchange in nearby Bendigo. These two mines, north of Flinders Ranges, SA; and Bendigo, NSW; became two points of investigation for my project.

I was invited to respond to the Australian waterways, but I became increasingly fascinated with the almost accidental parallel history of how one culture values one shimmering mineral over another shimmering mineral. My goal was to do a project that explored these seemingly arbitrary questions of economy in the hopes of appreciating [pun intended] an economic culture based on red-ochre in the same way the West appreciates the value of the similarly unpractical mineral of gold.

Like many things in aboriginal culture, it quickly became apparent that to understand trade and economy, I needed to better understand the clash over the pilgrimage itself and why the Diyari didn’t go around the fences or barter the path they took in any way to avoid conflict. So I found answers in the concept of the “songline,” also called the Walkabout, storyline or Dreaming Path.

My resources are predominantly [but not exclusively] the linguist and author Bruce Chatwin’s “The Songlines” and specifically his conversations with Father Flynn, a Rome ordained minister and the first Aboriginal to lead his mission; Dale Kerwin’s “Aboriginal Dreaming Paths and Trading Routes: The colonization of the Australian Economic Landscape”, Bill Gammage’s “The Biggest Estate on Earth”, and Victoria Finlay’s “Color, A Natural History of the Palette.”

Bill Grammage describes a songline as a historical path that records the recent past and connects it all the way back to one’s original ancestors and before, which they call the Dream time. The Dream time has to do with Aboriginal creation mythology and how the country came into being. It’s simultaneously the path of one’s totem [an ancestral lineage]; and geography expressed in songs, dances, paintings “animating its country, and ecological proof of the unity of things… [so it’s very much a map] Every particle of land, sea, and sky must lie on a songline; otherwise an ancestor can’t have created it, and it could not exist.” [Gammage, 2011]. So it intertwines the concrete world with memory, history and mythology.

When a child was conceived, they received a totem, or ancestral lineage, from their mother, but the child has two fathers. One is the biological father, and the other is a father who gives the child a spirit and the song that they will inherit. According to some, the baby’s first kick corresponds to the moment of “spirit-conception,” and the geographic location of origin where the mother notices a kick will determine the child’s second father, future song, dance, and land inheritance in minute detail [Gammons]. The child will often be given a wood or stone, “tjuringas,” which are deeds passed down generationally through this spirit lineage. Chatwin describes “the spirit-child conception as a kind of musical sperm where the child may claim paternity along the line of his footprints.”

Chatwin describes that the addition of a spirit-father would allow a family to have five full biological siblings with allegiances inside and outside the tribe as a way to address imbalances, feuds, or vendettas. Biological fathers were advised to find a wife by walking 2 or 3 ‘stops’ along their songline or the handover point where the song passed out of his ownership. Therefore the idea of invading their neighbor’s land would “never have entered their heads.” [Flynn]. This duality of paternal lineage became an issue in 1992 in the Mabo decision where the Australian government overturned a terra nullius doctrine by recognizing limited land rights of Murray Islanders in the Torres Straits upon proof of ownership, but didn’t recognize the land rights for a “spirit-child” of a non-biological parent even if it was the only parent the child knew. This was another blow dismantling the significant social fabric created by the First Nations people’s songlines.

To understand the historical significance of the songline and path is to realize that any pilgrimage was an act by descendants documenting history since the beginning of ancestral time. The songline is acted out through a ritual that may include a beginning-to-end song cycle. To perform this cycle involved an assembly of multiple totemic clan folks from numerous tribes, an event called the “Big Place” [or Corroborees]. “one after the other, each ‘owner’ of an inherited songline, would sing his stretch of the Ancestor’s footprints. Always in the correct sequence!” Because the performance was a sacred act, singing it out of order was a crime, punishable by death because it would “un-create the Creation”, and therefore undo history. Therefore, learning ones inherited section of the songline correctly [a kind of land right] was paramount and had to be performed without any deviation.

For the Aboriginals, everyone hoped to have at least four ways out of their location to travel away from their tribe in the event of a crisis. Therefore, “Every tribe — like it or not — had to cultivate relations with its neighbor.”

The old Wangkangurru warrior code and the old way of sorting out differences, face-to-face, Mungeranie, east of Lake Eyre South Australia, 1920.

The grandparents of these men shared a songline with the Diyari and likely met at Corroborees, traded goods and intermarried with them.

Many tribes settled disputes between men by throwing spears at each other's thighs, which they defended with small shields, until one was unable to stand.

Father Flynn said that when “White men [came to this continent they]… made the common mistake of assuming that, because the Aboriginals were wanderers, they could have no system of land tenure. This was nonsense. Aboriginals, it was true, could not imagine territory as a block of land hemmed in by frontiers: but rather as an interlocking network of ‘lines’ or ‘ways through’…,” and said that “all our words for “country”… are the same as the words for “lines.” Flynn also said that the word for “white man” is the same as the word for “meat” or sitting prey. This translation expresses the significance of survival being connected to movement, and the walkabouts, walking the songlines. Living immobile in fences was a death sentence.

Flynn says it’s quite similar to the birds because “Birds also sing their territorial boundaries.” So the idea of creating routes in which to move, songlines, or dreaming paths, was based on the practicality of being in motion for survival, but it also laid the foundation for arguably the most complex web of inter-continental commodity exchange, rules for marriage and incest taboos, dealing with cultural conflicts, land inheritance, etc. [There is some anthropological evidence of ancient cultures that literally walked the migration paths of the birds with a language that mimicked their sound, ie, bird songs.]

However, in terms of economy, there were formal rules for exchanging commodities and routes to trade. Flynn says songlines were “a kind of bush-telegraph-cum-stock-exchange, spreading messages between peoples who never saw each other, who might [otherwise] be unaware of the other’s existence.” This was not trade in the Western sense of buying and selling for profit.’ Because Aboriginals, in general, had the idea that all ‘goods’ were potentially malign and would work against their possessors unless they were forever in motion.

This is fascinating because although commodities in constant motion are the foundation of economic growth in Western economics today, for the first nations people the value is in the action, the exchange, the connection between people. “People liked nothing better than to barter useless things — or things they could supply for themselves: feathers, sacred objects, belts of human hair” and even umbilical cords. [which at the time of Chatwin’s text was absurdly useless but now is politically and medically highly charged with value]. “Trade goods” he continued,

“should be seen rather as the bargaining counters of a gigantic game, in which the whole continent was the gaming board and all its inhabitants players. ‘Goods’ were tokens of intent: to trade again, meet again, fix frontiers, intermarry, etc… A shell might travel from hand to hand… since time began [in the]… ceremonial centres where men of different tribes would gather.”

In the West, a gold wedding ring that’s passed down from generation to generation is also highly prized in Western culture.

While trade existed on friendly soil, when no mutual songlines, totems, or languages were shared, trade created peace in potentially hostile territories. Sign language also supplemented language and songs.

“The trade route is the songline… because songs, not things, are the principal medium of exchange. Trading in “things” is the secondary consequence of trading in song.’… “no one in Australia was landless, since everyone inherited, as his or her private property, a stretch of the Ancestor’s song and the stretch of country over which the song passed. A man’s verses were his title deeds to territory. He could lend them to others. He could borrow other verses in return. The one thing he couldn’t do was sell or get rid of them.”

In South Australia, four major commerce routes intersect. Additionally, at these meetings [corroborees or Big Place], hundreds of people may gather for days [performing rituals, settling disputes, and arranging marriages]. Corroborees can be simply about entertainment or morality, emphasizing education or introducing new techniques or commodities. Men will exchange and acquire ritual knowledge and secrets, and expand his song-map by swapping songs, dances, sons and daughters, and grant each other ‘rights of way’.

“Songlines are places of refuge, comfort, and communion [affirming]… a message [that] the universe is one; all creation has a duty to maintain it; at the risk of your soul keep things as they are.” In other words the “whole countryside is [a] living, age-old family tree.” [Gammons, 131]

Additionally, “..every song cycle went leap-frogging through twenty languages, and [may] start in the north-west, near Broome and go on to ..the sea near Adelaide”… and yet it’s the same song. People recognize the tune, which is always the same, even though the language, words, and meaning will change.”

INTER CONNECTED CULTURE, TRADE AND LAND MANAGEMENT

Imagine six hundred songlines weaving and interconnecting creating 1200 handover points’ marked by dots around the perimeter. Each ‘stop’ had been sung into position by a Dreamtime ancestor and therfore its place on the song-map couldn’t be moved. But since each was the work of a different ancestor, they didn’t line up to form a modern idea of a political frontier. [Flynn]

Songlines connected people separated by sometimes thousands of kilometres. “The native cat song went across language boundaries through” below Port Augusta to the Centre; another from Kimberley to the Centre to Uluru to Cairns. In 1882 Queensland, Carl Lumholts heard the same song in different languages 800 kilometers apart. [Unfortunately, many of these maps are traced only through the decimation caused by smallpox throughout the continent after the settler’s arrival.]

Songlines were also a recording system for mapping the land management of the country. In turn, land management systems provided time for people to pursue and practice the arts and religious customs that also referred to their songlines, dreams, and totems. Gammage’s 2011 book “The Biggest Estate on Earth” postulates that indigenous Australia was an interconnected estate with cross-continental trade and land management that first national people fully controlled, making plants and animals abundant, convenient, and predictable. He cites many examples of vegetation and soil impossibilities in the European landscape that were nonetheless flourishing by virtue of the technical evolution of aboriginal land management. Bushfires [fire and stick farming] were central land management, and Aboriginals used fires to attract game. But also, through controlling the vegetation, shelter, and habits such as hibernation of animals, they ensured that animals would multiply and always be available. They also shared more extensive scale management needs of their neighbors through their totem and Dreaming links [songlines]. This directly opposes European notions about them as hunter-gatherers: “They traveled to known resources, and made them not merely sustainable, but abundant, convenient and predictable,… Clans could spread resources over large areas, thereby better providing for adverse seasons (with allies)… sometimes hundreds of kilometers away, who could trade or give refuge. They were thus ruled less by nature’s whims, than (Western) farmers.” He also argues that only in Australia could grazing animals, such as sheep, be shepherded via bushfire because they had no predators [aside from humans].

The songline running through the sheep farms brings me back to the story of the ochre war.

++

LEFT: Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters) by Tjungkara Ken, Yaritji Young, Maringka Tunkin, Freda Brady and Sandra Ken, Tjala Arts. Photograph: George Serras/National Museum of Australia. 2015.

RIGHT: Songlines by Jen Baily, Acrylic Traditional Kamilari Dot painting, 60x55cm (date unknown, contemporary). Colors are traditional colors found at Flinders Ranges.

DYARI, DIYARI, DIERI, DIEYERIE

Trade routes were based on the movement of the ancestors. The Diyari was a respected and feared tribe in the Central region where several significant trade routes met and part of the Diyari path that connected a single song, “Two Dog,” ran nearly 2,000 km from NE Queensland to Port Augusta. This path, in turn, connected Western Australia, Queensland, and NSW to South Australia, over 3,000 kilometers of territory. This communication was advantageous for acquiring intellectual knowledge and spiritual objects such as engraved pearl shells, the oval baler-shell ornaments [Kerwin, 63]. In addition to trading secrets, songs, and sacred items such as pituri [tobacco], ochre, and shells, they had access to intercontinental items available, including spears, shields, possum skin cloaks, animal nets, and traps, belts, medical resources, gum cements, string bags, boomerangs, baskets, grinding dishes, bags, and digging sticks.

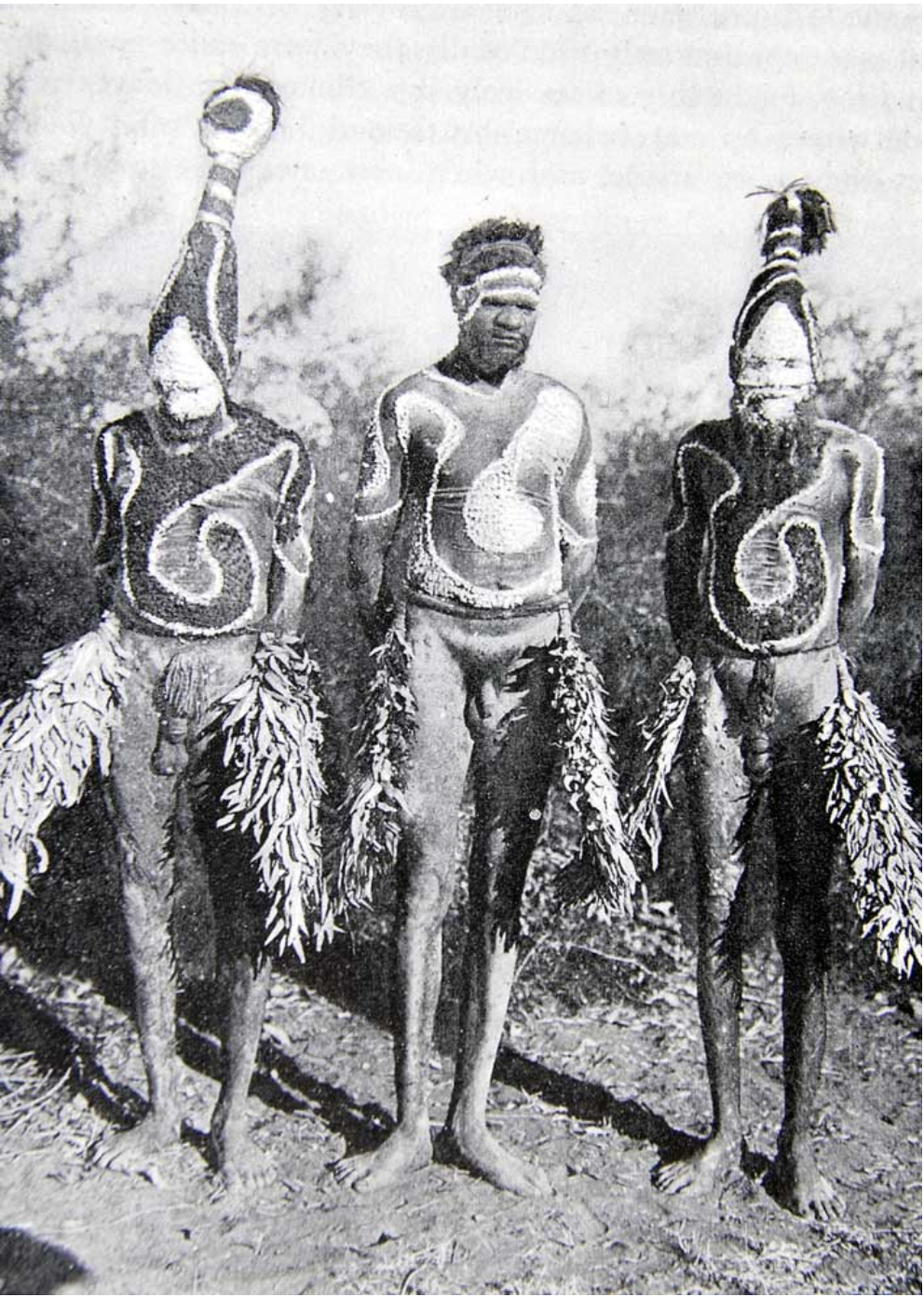

RIGHT: Funeral Ceremonial painting of Tiwi Tribesmen.

LEFT: Ceremony of the Wind Totem - Warramunga Tribe

RITUALS AND MYTH

“Red ochre is the most critical trading item used in rock art, wooden and stone material culture, on fur products, and to adorn the body during Corroborrees and spiritual ceremonies, such as weddings. Primary Aboriginal mining sites include Parachilna in Flinders Ranges by the Diyari of Lake Eyre, and at Kenniff Cave in Queensland, both possibly dated nearly 20,000 years ago, and another site in Western Australia mined on a grand scale. All aboriginal nations had ochre for everyday life, but the best came from these specific sites and were treasured for ceremonial purposes.

The Diyari traded the sacred red ochre, karku, [meaning the blood of the emu]. AP Elkin, an anthropologist from the 1930s, traced a songline of the Mindari from Queensland to Port Augusta (the southern part of South Australia) that describes the geological features of Two-Dogs. The songline related to the red-ochre mine describes the mythological ancestral emu, Kuringii [Kuringai]. Two ancestral dingoes chased the Kuringii down to Cooper Creek and Mount Alick, where it changed into a mountain to fight the dingoes before turning east. While in full flight, Kuringii met a man with a pack of dingoes at the foot of the Flinders Ranges led by a ferocious dog. After an epic battle, the dingoes and the man killed the Kuringii. The man turned into a hill, and the dingoes rested, finding a cave called Jerinna until they died and turned into limestone boulders. Other dingoes turned into high peaks, while the Kuringii’s blood became the sacred red ochre.

There are other versions of the origins.

Supposedly the musical tune was the same through various languages and interpretations. Even though this is only a few hundred-kilometer stretches, the melody stayed consistent from Queensland to Port Augusta, continually describing these landmarks.

To finish up the story of the Ochre Wars, the English administrators in Adelaide wanted to stop the violence between the sheep farmers and the Diyari. Since the British couldn’t prevent the Diyari from going to the ochre mines in Parachilna, they concocted the outrageous scheme of bringing the entire mine to the Diyari tribe in Lake Eyre. No transport company would take on the project as it was an impossible task for ox carts. However stragically, the first real problem in this whole scheme is that the prized value of the red-ochre was not only its unique shimmery texture, the value came from the Diyari’s exclusive knowledge of its location and extracting techniques. This secret is what gave the Diyari a high status in the region.

The second problem with the Adelaide scheme is that in 1874, they moved the wrong mine! Because no Westerner was capable of removing the mine from Parachilna, laborers spent weeks moving four tons of red-ochre in harsh 19th-century South Australian conditions from a mine belonging to the Kaura people along the coast near Adelaide. They hauled the four tons by cart, 700 km up to Lake Eyre. Not believing the Diyari would know the difference in the quality of the ochre, they persuaded German missionaries to distribute the ochre to the Diyari. However, as Victoria Finlay states:

Trading happens when one item is seen to be almost equal in value to another. What value did free paint have? It wouldn’t have bought very many precious pearl shells from the Kimberley coast, nor would it have bought much of the pituri tobacco the Diyari people were so keen to buy from other tribes. The recipe for making pituri leaves into a super-narcotic was a secret, kept only by the elders of certain tribes, so swapping ochre for pituri was swapping a secret for a secret and therefore appropriate. If the Lake Eyre tribes were denied sacred ochre then it would mean they were not able to play their part in the complex trading network that Aboriginal tribes depended on.

Lyndhurst, South Australia.